The Drongo, Interview #4: Lyla Boyajian

by Maxwell Joslyn. .

Hello again, all you drongos. The Drongo continues to drong-grow: 18 subscribers received the first interview, but now there are 34 of you.

Our lineup of interviewees stretches all the way to June. Thank you so much for reading -- keep doing it!

Receive new interviews by email, twice a month. Subscribe to The Drongo today: it's free!

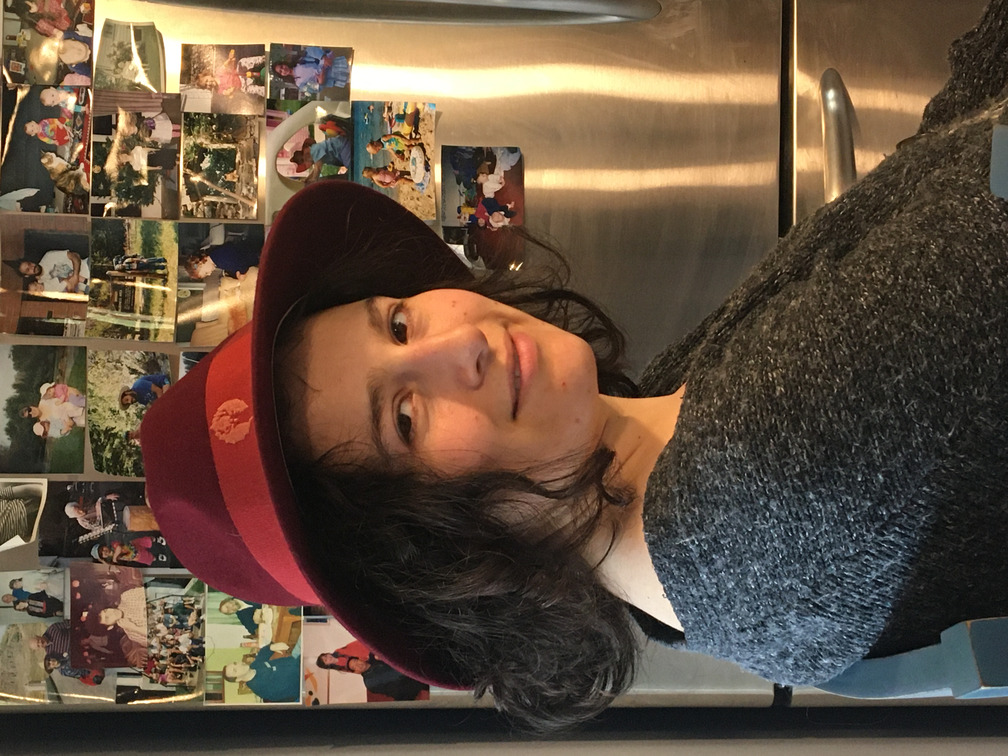

The Drongo: Today on The Drongo, our guest is Lyla Boyajian. She's one of the most energetic people I know, and if she's not a drongo, nobody is. You'll see.

Who exactly are you, Lyla?

Lyla Boyajian: I'm from Chichester, New Hampshire, and I studied Spanish at Reed College. I moved back home and spent a year recruiting for the 2020 Census. I'm currently working for the NH Bar’s Pro Bono Program before I start a delayed Fulbright in Armenia next spring. After that, law school. I've also been studying Russian for the past 4 years.

Fun facts:

- Once, Medvedev's car almost ran down me and my Iranian friend, which would have been an international nightmare.

- I make a bomb creme brulee.

- During Reed College's annual Renn Fayre, I hit a home run in the softball game.

The Drongo: Let's start off with your narrow miss. I want to hear about you almost getting run down by Medvedev.

Lyla Boyajian: In the fall of 2017, I participated in Birthright Armenia.

One of my internships was at the Ari Literature Foundation. I worked there with another Birthright volunteer named Arineh, who was from Iran. On our first day there, one of the internship coordinators brought us in a taxi to meet our supervisor. The ride was awkward, to say the least. Neither of us had been friends with anyone from the other's country before. However, we stuck it out, and, by the end of our lunch break, we'd discovered that we were both massive fans of Jane Austen and became quick friends.

Arineh was really interested in asking me about the US, and I was fascinated by the way she described her professors getting around bans on teaching feminism: apparently, you can teach feminism as a way that others interpret texts, so long as you yourself aren't actively espousing it. Over the course of our internship, we both learned a lot from each other. Although neither of us could have visited each other in our home countries, Armenia provided a neutral meeting ground. It also turned out that our host families lived in the same neighborhood, so we would often walk home from work or Birthright events together, feverishly talking about English literature.

On one of those days, we came upon a crosswalk on Yerevan's main drag. We had the walk light and there were no cars in sight, so we started across. As we reached the middle of the crosswalk, a police officer on the other side ran up to us, grabbed us, and pulled us to the sidewalk just before a motorcade blew through the intersection. We didn't think much of it, but when I got home, I saw that my host mom and sister were watching the news. There on the TV was the same limousine that had almost run us down -- apparently, Medvedev had just arrived from Moscow.

That police officer prevented what I'm sure would have been a massive international headache. The headlines would have read: "Iranian and American citizens killed by Russian PM -- What Does This Mean for Nuclear Deal?"

The Drongo: I hope you continue to avoid causing international incidents when you return to Armenia on your grant program. Speaking of which, I heartily congratulate you on earning a Fulbright!

Lyla Boyajian: Thank you!

The Drongo: Why Armenia, and what will be the focus of your time there? On this question, especially, please hold absolutely nothing back.

Lyla Boyajian: I value my relationship with my ancestral homeland, and I knew there was so much more for me to do there. I feel a sense of connection to the land and the people that is hard to explain, but that I think most people experience when they return to the place that is the source of their ethnic or cultural heritage. I didn't grow up in an Armenian community, so at first, the whole country reminded me of visiting my grandparents' house as a kid, which contributed to a false sense of security. Luckily, Armenia is a very safe place, so I was fine.

After my experience with Birthright, I knew that I wanted to return. I spent a year back at home with my family and applied for the Fulbright. My grant year was postponed because of the pandemic. Nevertheless, I am excited. I hope that by the time I get there, I will be able to have a more traditional Fulbright experience.

I have an English Teaching Assistant grant, so I'll be helping out in the English department of a university in Yerevan. That's all the information I have so far. The start date was pushed back until next August, so I'm sure I'll learn more as we get closer.

I also put in a proposal to do an independent project on the way that Argentine tango is used in the Armenian diaspora, in repatriate communities, and as a tool of international diplomacy. There's a sizable Armenian diaspora in Argentina, so when some of those people moved back in the last few decades, they brought tango back with them. There's now a decent tango scene in Yerevan, and the Argentine embassy holds a yearly festival to encourage tango dancing. I didn't have the self-confidence to go out dancing while I was last there, but that's changed. I'm hoping that we will be able to dance again, at least in the second semester of my grant. I'm also looking forward to continuing to improve my Armenian and Russian.

The Drongo: You'll have quite the packed schedule when you return, but I know you'll cherish every second.

Let's mentally transport ourselves from your ancestral homeland to the land of your birth: the good old USA. In our pre-interview discussion, you specifically mentioned the weirdness of working for the US Census. What was weird about it? The work environment? The duties? The canvassing of countless strangers?

Lyla Boyajian: First, let me say that the census may have been the ideal job for me out of college. It was active, different every day, and challenging. I made a lot of money, and I also got to speak Spanish on occasion. And, despite the bureaucracy, I generally believed that what I was doing would make a difference.

I was not an enumerator (census taker), but rather a recruiter, and then a census response representative. I was responsible for recruiting more than 1,000 applicants over the course of six and a half months. I started with most of the towns in my area, then took over the county next to us as well. Twice a week I spoke at the employment office, and I held office hours at local libraries and booths at craft fairs. We also spent at least two days a week blitzing. That meant going door-to-door in neighborhoods where we were low on applicants, as well as asking every business to let us hang up a flyer. We had a map app called MOJO that was like God.

Each neighborhood had a number of applicants needed, broken down by languages spoken, and we had to reach at least 80% of that goal. We were constantly understaffed: a large contingent of people quit because Massachusetts was getting paid more. All I can say is that Massachusetts has income and sales taxes, while NH has neither. We ended up getting a raise after that to help with recruiting, anyway.

Honestly, most of my job was explaining what the census is, and convincing people that they could work for a few weeks to make some extra cash. We also did county-bounce blitzing, which was when we brought everyone who was available to a county that was low, where they worked for at least three days just on blitzing. In one day, you might walk 10 miles.

I often worked alone, although I made friends with other recruiters, and we would take turns helping each other in our territories. The census had the most diverse team I've ever worked in, and I really appreciated being able to meet people who were part of so many different communities, and who had had such different experiences. One of my coworkers and friends had worked for the UN and was now retired; another volunteered with AA at a local prison; and still others had immigrated from Nepal, Turkey, or Rwanda. New Hampshire is a small state, but it has a lot of mountains, so travel still takes up time. With the census, I got paid for drive time and reimbursed for mileage. I love driving and listening to music, so that was pretty ideal for me.

After the pandemic hit, we started working from home, taking the census from people who were calling in to respond. As soon as our office opened, I was brought in to help as a secretary there, which was totally different from recruiting. At that point, we were hiring, so I was helping people schedule fingerprinting appointments, and directing calls all over the place. We had to hire thousands of workers in a month.

In July, we started going out to live events where anyone could respond to the census, and I was able to help with that. I particularly enjoyed working with Spanish speakers. However, it was obviously dangerous work. Despite guidelines for me as a federal worker, nothing stopped anti-maskers from harassing me and telling me I was slowly suffocating myself. I do think I convinced one person that COVID is real. He asked me if I even knew anyone who'd had it, and I told him about my cousin and her husband. They are fine now, but got pretty sick with it in April. He was genuinely shocked, and gave up the conspiracy theories.

I guess that's one of the things about the census: there's intentionally no filter on who you interact with, so I got to see a broad sample of the people in my state. Some of them were highly educated and fabulously wealthy. One man I met had never learned to read. Some were recent immigrants, and some had had ties to the land for millennia or centuries. Some of them would pull me aside and say they were only taking the census to make sure that they counted and "the illegals" didn't; others would have long conversations with me about whether or not they could ethically work the census knowing that undocumented people might be discriminated against. Surprisingly, people were overwhelmingly kind to me. I had one creepy run-in that I effectively dealt with, and my boss and coworkers were supportive. We used my experience to better prepare future census workers in that area.

As a side note, one of the people I recruited was my boyfriend, who doesn't fit the typical retiree demographic of most census workers. He had a very different experience than I did. He did the door-to-door thing, but he was assigned most of the addresses that other census workers couldn't physically get to. On numerous occasions, he told me he'd followed his GPS through the woods for hours, only to find an abandoned building, or no building on the site at all. Then, he would have to hike back out of the woods, trying to find someone to confirm that there was no structure there. Very weird.

The Drongo: Weird, indeed, but I'm glad to know that the census has drongos like your boyfriend to trek through the woods on demand.

The Fulbright isn't the first famous organization which you've convinced to do something for you. I have it on good authority that, way back in high school, you convinced the Freemasons to do you a favor. To conclude our interview, please tell that story.

Lyla Boyajian: Oh, yes! I'm surprised you didn't ask me about the lumber smugglers--

The Drongo: The what?!

Lyla Boyajian: --but the Freemasons are good people as far as I could tell. Let's give them some airtime.

When I was a junior in high school, I was invited to attend a youth leadership workshop in the UK. My parents, thinking it would never happen, told me I could go if the school agreed and I funded it myself. Well, my headmaster sent out an announcement before he even told me I could have the days off, so the challenge came down to funding my travels. I did some research and found out that "building leadership skills and international connections" is part of the mission of the Freemasons.

I wrote letters to every Masonic lodge I could find in my state, and many of them invited me to speak at open meetings. I would go and speak to them, and they gave me a check -- generally $50 to $200. One of the Masons was married to someone in the NH Federation of Women's Clubs, so they kicked in $400 without me even having to ask. On one occasion, an official from the Grand Lodge was there to impart a lifetime achievement award. He shook my hand and slipped me a hundred-dollar bill.

It was a really lovely experience, and I got to go to the conference in the end.

The Drongo: Wheeling and dealing with a secret society? It doesn't get more drongo than that. I love it!

Lyla, thanks so much for participating in an interview with The Drongo. I wish you a whole raft of adventures, in Armenia and beyond.

Lyla Boyajian: Thank you so much for doing this! This has been a lovely exercise in self-reflection, and I can't wait to read everyone else's interviews. <3

The Drongo: Lyla Boyajian, everybody! If you didn't get enough of her on The Drongo, you can also follow her on Instagram at @ohlyler, or find her on Facebook.

ⵘ ⵗ ⵘ ⵗ ⵘ

If you liked this interview with Lyla, please share it on social media.

https://www.maxwelljoslyn.com/thedrongo/interviews/lyla-boyajian

If you aren't already subscribed to The Drongo, subscribe today to receive more interviews by email. The next interview, with Nick LeFlohic, will be released in early March. See you next time!